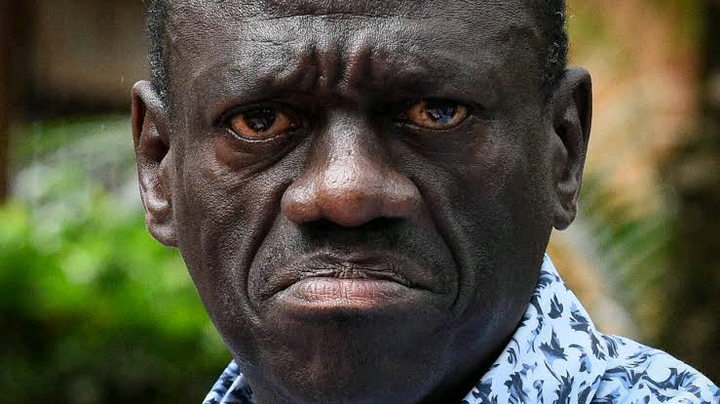

Veteran Ugandan opposition leader Dr Kizza Besigye has been advised to negotiate with President Yoweri Museveni if he wants to regain his freedom.This advice comes from a retired bush war general who claims that Besigye has no other option but to betray the struggle for change if he hopes to walk free.

Besigye and his aide, Hajj Obeid Lutale Kamulegeya, have spent more than six months in detention after being abducted from Nairobi, Kenya, in November 2024.The two were in Nairobi to attend the launch of Kenyan politician Martha Karua’s book when they were arrested and transported to Uganda.

In February 2025, Uganda’s Director of Public Prosecutions Jane Frances Abodo charged Besigye, Kamulegeya, and Captain Denis Oola with treason.

The state accuses them of plotting to overthrow the Ugandan government through military and logistical means.The charge sheet alleges that between 2023 and November 2024, the trio conspired in Geneva, Athens, Nairobi, and Kampala to topple the government.

They are said to have held meetings, both in person and virtually, with foreign and local individuals to mobilize support for their alleged plan.

Besigye is further accused of organizing Ugandans to receive training in Kenya and of seeking military and financial support to destabilize Uganda.

With trial delays and political pressure mounting, the call to negotiate with Museveni signals the government’s possible willingness to strike a deal if Besigye is ready to compromise.